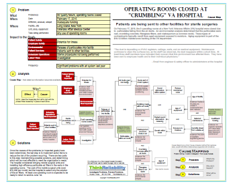

On February 17, 2016, the 5 operating rooms at a New York Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital were closed due to particulates falling from the air ducts. An internal email from the engineer & safety officer to administrators at the hospital described the problem as this: “The dust is depositing on HVAC registers, ceilings, walls, and on medical equipment. Maintenance continues to clean the surfaces but, as the staff has observed, the dust reappears within a short time. At least three staff members have indicated their concern that this environment has affected them. They have been sent to employee health and to their individual physicians.”

The second step of the process is the analysis: determining why these goals were impacted. The release of the particulates into the facility is because there are particulates within the air ducts, and the air ducts open into the facility to provide heating, ventilation and air conditioning. In order to determine where the particulates come from, first it must be determined what they are composed of. An environmental analysis determined that the particulates were rust, crumbling concrete, fiberglass fibers, and cladosporium (a common mold).

The analysis also identified that rust in air systems typically results from aged equipment exposed to moisture. Cladosporium also results from exposure to moisture. The air duct system pulls in outside air, including humidity, resulting in the system being exposed to moisture. The VA hospital is 45 years old, which actually makes it one of the “newer” VA facilities. (According to the VA, about 60% of its facilities are more than 60 years old.) While it’s unclear what maintenance or replacements have been performed on these components over the life of the facility, deferred maintenance is a general problem at VA facilities. According to the VA inspector general, there is a $10-12 billion maintenance backlog at the department.

Once the causes of the problems (or impacted goals) have been determined, the last step is to implement action items to reduce the risk of the problem recurring. There are two parts to this step: brainstorming possible solutions, and determining which will be most effective to meet the organization’s needs. The hospital considered bringing in mobile surgical units and installing high efficiency particulate air filters in the vents in the operating rooms. The cost of the mobile surgical units (over $70,000 per month) led the hospital to select only the solution of the air filters. At least one operating room is expected to be ready to return to service June 1st.

To view a one-page downloadable PDF of the incident investigation, including the impacted goals, analysis with evidence, and possible solutions, please click on “Download PDF” above.